Psychiatry

| |

| Focus | Mental health |

|---|---|

| Subdivisions | Neuropsychiatry, biological psychiatry, social psychiatry, interventional psychiatry |

| Significant diseases | Schizophrenia, mood, impulse-control, eating, neurodevelopmental, personality, substance use disorders |

| Significant tests | Mental status examination, psychological, cognitive, personality tests |

| Specialist | Psychiatrist |

| Glossary | Glossary of psychiatry |

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of deleterious mental conditions.[1][2] These include various matters related to mood, behaviour, cognition, perceptions, and emotions.

Initial psychiatric assessment of a person begins with creating a case history and conducting a mental status examination. Physical examinations, psychological tests, and laboratory tests may be conducted. On occasion, neuroimaging or other neurophysiological studies are performed.[3] Mental disorders are diagnosed in accordance with diagnostic manuals such as the International Classification of Diseases (ICD),[4] edited by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5), published in May 2013, reorganized the categories of disorders and added newer information and insights consistent with current research.[5]

Treatment may include psychotropics (psychiatric medicines), interventional approaches and psychotherapy,[6][7] and also other modalities such as assertive community treatment, community reinforcement, substance-abuse treatment, and supported employment. Treatment may be delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis, depending on the severity of functional impairment or risk to the individual or community. Research within psychiatry is conducted on an interdisciplinary basis with other professionals, such as epidemiologists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists, and clinical psychologists.

Etymology

[edit]

The term psychiatry was first coined by the German physician Johann Christian Reil in 1808 and literally means the 'medical treatment of the soul' (ψυχή psych- 'soul' from Ancient Greek psykhē 'soul'; -iatry 'medical treatment' from Gk. ιατρικός iātrikos 'medical' from ιάσθαι iāsthai 'to heal'). A medical doctor specializing in psychiatry is a psychiatrist (for a historical overview, see: Timeline of psychiatry).

Theory and focus

[edit]"Psychiatry, more than any other branch of medicine, forces its practitioners to wrestle with the nature of evidence, the validity of introspection, problems in communication, and other long-standing philosophical issues" (Guze, 1992, p.4).

Psychiatry refers to a field of medicine focused specifically on the mind, aiming to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders in humans.[10][11][12] It has been described as an intermediary between the world from a social context and the world from the perspective of those who are mentally ill.[13]

People who specialize in psychiatry often differ from most other mental health professionals and physicians in that they must be familiar with both the social and biological sciences.[11] The discipline studies the operations of different organs and body systems as classified by the patient's subjective experiences and the objective physiology of the patient. [14] Psychiatry treats mental disorders, which are conventionally divided into three general categories: mental illnesses, severe learning disabilities, and personality disorders.[15] Although the focus of psychiatry has changed little over time, the diagnostic and treatment processes have evolved dramatically and continue to do so. Since the late 20th century, the field of psychiatry has continued to become more biological and less conceptually isolated from other medical fields.[16]

Scope of practice

[edit]

Though the medical specialty of psychiatry uses research in the field of neuroscience, psychology, medicine, biology, biochemistry, and pharmacology,[17] it has generally been considered a middle ground between neurology and psychology.[18] Because psychiatry and neurology are deeply intertwined medical specialties, all certification for both specialties and for their subspecialties is offered by a single board, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, one of the member boards of the American Board of Medical Specialties.[19] Unlike other physicians and neurologists, psychiatrists specialize in the doctor–patient relationship and are trained to varying extents in the use of psychotherapy and other therapeutic communication techniques.[18] Psychiatrists also differ from psychologists in that they are physicians and have post-graduate training called residency (usually four to five years) in psychiatry; the quality and thoroughness of their graduate medical training is identical to that of all other physicians.[20] Psychiatrists can therefore counsel patients, prescribe medication, order laboratory tests, order neuroimaging, and conduct physical examinations.[3] As well, some psychiatrists are trained in interventional psychiatry and can deliver interventional treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy, transcranial magnetic stimulation, vagus nerve stimulation and ketamine.[21]

Ethics

[edit]The World Psychiatric Association issues an ethical code to govern the conduct of psychiatrists (like other purveyors of professional ethics). The psychiatric code of ethics, first set forth through the Declaration of Hawaii in 1977 has been expanded through a 1983 Vienna update and in the broader Madrid Declaration in 1996. The code was further revised during the organization's general assemblies in 1999, 2002, 2005, and 2011.[22]

The World Psychiatric Association code covers such matters as confidentiality, the death penalty, ethnic or cultural discrimination,[22] euthanasia, genetics, the human dignity of incapacitated patients, media relations, organ transplantation, patient assessment, research ethics, sex selection,[23] torture,[24][25] and up-to-date knowledge.

In establishing such ethical codes, the profession has responded to a number of controversies about the practice of psychiatry, for example, surrounding the use of lobotomy and electroconvulsive therapy.

Discredited psychiatrists who operated outside the norms of medical ethics include Harry Bailey, Donald Ewen Cameron, Samuel A. Cartwright, Henry Cotton, and Andrei Snezhnevsky.[26][page needed]

Approaches

[edit]Psychiatric illnesses can be conceptualised in a number of different ways. The biomedical approach examines signs and symptoms and compares them with diagnostic criteria. Mental illness can be assessed, conversely, through a narrative which tries to incorporate symptoms into a meaningful life history and to frame them as responses to external conditions. Both approaches are important in the field of psychiatry[27] but have not sufficiently reconciled to settle controversy over either the selection of a psychiatric paradigm or the specification of psychopathology. The notion of a "biopsychosocial model" is often used to underline the multifactorial nature of clinical impairment.[28][29][30] In this notion the word model is not used in a strictly scientific way though.[28] Alternatively, a Niall McLaren acknowledges the physiological basis for the mind's existence but identifies cognition as an irreducible and independent realm in which disorder may occur.[28][29][30] The biocognitive approach includes a mentalist etiology and provides a natural dualist (i.e., non-spiritual) revision of the biopsychosocial view, reflecting the efforts of Australian psychiatrist Niall McLaren to bring the discipline into scientific maturity in accordance with the paradigmatic standards of philosopher Thomas Kuhn.[28][29][30]

Once a medical professional diagnoses a patient there are numerous ways that they could choose to treat the patient. Often psychiatrists will develop a treatment strategy that incorporates different facets of different approaches into one. Drug prescriptions are very commonly written to be regimented to patients along with any therapy they receive. There are three major pillars of psychotherapy that treatment strategies are most regularly drawn from. Humanistic psychology attempts to put the "whole" of the patient in perspective; it also focuses on self exploration.[31] Behaviorism is a therapeutic school of thought that elects to focus solely on real and observable events, rather than mining the unconscious or subconscious. Psychoanalysis, on the other hand, concentrates its dealings on early childhood, irrational drives, the unconscious, and conflict between conscious and unconscious streams.[32]

Practitioners

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (August 2017) |

All physicians can diagnose mental disorders and prescribe treatments utilizing principles of psychiatry. Psychiatrists are trained physicians who specialize in psychiatry and are certified to treat mental illness. They may treat outpatients, inpatients, or both; they may practice as solo practitioners or as members of groups; they may be self-employed, be members of partnerships, or be employees of governmental, academic, nonprofit, or for-profit entities; employees of hospitals; they may treat military personnel as civilians or as members of the military; and in any of these settings they may function as clinicians, researchers, teachers, or some combination of these. Although psychiatrists may also go through significant training to conduct psychotherapy, psychoanalysis or cognitive behavioral therapy, it is their training as physicians that differentiates them from other mental health professionals.

As a career choice in the US

[edit]Psychiatry was not a popular career choice among medical students, even though medical school placements are rated favorably.[33] This has resulted in a significant shortage of psychiatrists in the United States and elsewhere.[34] Strategies to address this shortfall have included the use of short 'taster' placements early in the medical school curriculum[33] and attempts to extend psychiatry services further using telemedicine technologies and other methods.[35] Recently, however, there has been an increase in the number of medical students entering into a psychiatry residency. There are several reasons for this surge, including the intriguing nature of the field, growing interest in genetic biomarkers involved in psychiatric diagnoses, and newer pharmaceuticals on the drug market to treat psychiatric illnesses.[36]

Subspecialties

[edit]The field of psychiatry has many subspecialties that require additional training and certification by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN). Such subspecialties include:[37]

- Addiction psychiatry, addiction medicine

- Brain injury medicine[38][39]

- Child and adolescent psychiatry

- Consultation-liaison psychiatry[40]

- Forensic psychiatry

- Geriatric psychiatry

- Hospice and palliative medicine

- Sleep medicine[41]

Additional psychiatry subspecialties, for which the ABPN does not provide formal certification, include:[42]

- Biological psychiatry

- Community psychiatry

- Cross-cultural psychiatry

- Emergency psychiatry

- Evolutionary psychiatry

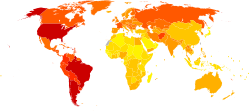

- Global mental health

- Learning disabilities

- Military psychiatry

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- Neuropsychiatry

- Interventional Psychiatry

- Social psychiatry

Addiction psychiatry focuses on evaluation and treatment of individuals with alcohol, drug, or other substance-related disorders, and of individuals with dual diagnosis of substance-related and other psychiatric disorders. Biological psychiatry is an approach to psychiatry that aims to understand mental disorders in terms of the biological function of the nervous system. Child and adolescent psychiatry is the branch of psychiatry that specializes in work with children, teenagers, and their families. Community psychiatry is an approach that reflects an inclusive public health perspective and is practiced in community mental health services.[43] Cross-cultural psychiatry is a branch of psychiatry concerned with the cultural and ethnic context of mental disorder and psychiatric services. Emergency psychiatry is the clinical application of psychiatry in emergency settings. Forensic psychiatry utilizes medical science generally, and psychiatric knowledge and assessment methods in particular, to help answer legal questions. Geriatric psychiatry is a branch of psychiatry dealing with the study, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders in the elderly. Global mental health is an area of study, research and practice that places a priority on improving mental health and achieving equity in mental health for all people worldwide,[44] although some scholars consider it to be a neo-colonial, culturally insensitive project.[45][46][47][48] Liaison psychiatry is the branch of psychiatry that specializes in the interface between other medical specialties and psychiatry. Military psychiatry covers special aspects of psychiatry and mental disorders within the military context. Neuropsychiatry is a branch of medicine dealing with mental disorders attributable to diseases of the nervous system. Social psychiatry is a branch of psychiatry that focuses on the interpersonal and cultural context of mental disorder and mental well-being.

In larger healthcare organizations, psychiatrists often serve in senior management roles, where they are responsible for the efficient and effective delivery of mental health services for the organization's constituents. For example, the Chief of Mental Health Services at most VA medical centers is usually a psychiatrist, although psychologists occasionally are selected for the position as well.[citation needed]

In the United States, psychiatry is one of the few specialties which qualify for further education and board-certification in pain medicine, palliative medicine, and sleep medicine.

Research

[edit]Psychiatric research is, by its very nature, interdisciplinary; combining social, biological and psychological perspectives in attempt to understand the nature and treatment of mental disorders.[49] Clinical and research psychiatrists study basic and clinical psychiatric topics at research institutions and publish articles in journals.[17][50][51][52] Under the supervision of institutional review boards, psychiatric clinical researchers look at topics such as neuroimaging, genetics, and psychopharmacology in order to enhance diagnostic validity and reliability, to discover new treatment methods, and to classify new mental disorders.[53][page needed]

Clinical application

[edit]Diagnostic systems

[edit]Psychiatric diagnoses take place in a wide variety of settings and are performed by many different health professionals. Therefore, the diagnostic procedure may vary greatly based upon these factors. Typically, though, a psychiatric diagnosis utilizes a differential diagnosis procedure where a mental status examination and physical examination is conducted, with pathological, psychopathological or psychosocial histories obtained, and sometimes neuroimages or other neurophysiological measurements are taken, or personality tests or cognitive tests administered.[54][55][56][57][58] In some cases, a brain scan might be used to rule out other medical illnesses, but at this time relying on brain scans alone cannot accurately diagnose a mental illness or tell the risk of getting a mental illness in the future.[59] Some clinicians are beginning to utilize genetics[60][61][62] and automated speech assessment[63] during the diagnostic process but on the whole these remain research topics.

Potential use of MRI/fMRI in diagnosis

[edit]In 2018, the American Psychological Association commissioned a review to reach a consensus on whether modern clinical MRI/fMRI will be able to be used in the diagnosis of mental health disorders. The criteria presented by the APA stated that the biomarkers used in diagnosis should:

- "have a sensitivity of at least 80% for detecting a particular psychiatric disorder"

- "should have a specificity of at least 80% for distinguishing this disorder from other psychiatric or medical disorders"

- "should be reliable, reproducible, and ideally be noninvasive, simple to perform, and inexpensive"

- "proposed biomarkers should be verified by 2 independent studies each by a different investigator and different population samples and published in a peer-reviewed journal"

The review concluded that although neuroimaging diagnosis may technically be feasible, very large studies are needed to evaluate specific biomarkers which were not available.[64]

Diagnostic manuals

[edit]Three main diagnostic manuals used to classify mental health conditions are in use today. The ICD-11 is produced and published by the World Health Organization, includes a section on psychiatric conditions, and is used worldwide.[65] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, produced and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), is primarily focused on mental health conditions and is the main classification tool in the United States.[66] It is currently in its fifth revised edition and is also used worldwide.[66] The Chinese Society of Psychiatry has also produced a diagnostic manual, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.[67]

The stated intention of diagnostic manuals is typically to develop replicable and clinically useful categories and criteria, to facilitate consensus and agreed upon standards, whilst being atheoretical as regards etiology.[66][68] However, the categories are nevertheless based on particular psychiatric theories and data; they are broad and often specified by numerous possible combinations of symptoms, and many of the categories overlap in symptomology or typically occur together.[69] While originally intended only as a guide for experienced clinicians trained in its use, the nomenclature is now widely used by clinicians, administrators and insurance companies in many countries.[70]

The DSM has attracted praise for standardizing psychiatric diagnostic categories and criteria. It has also attracted controversy and criticism. Some critics argue that the DSM represents an unscientific system that enshrines the opinions of a few powerful psychiatrists. There are ongoing issues concerning the validity and reliability of the diagnostic categories; the reliance on superficial symptoms; the use of artificial dividing lines between categories and from 'normality'; possible cultural bias; medicalization of human distress and financial conflicts of interest, including with the practice of psychiatrists and with the pharmaceutical industry; political controversies about the inclusion or exclusion of diagnoses from the manual, in general or in regard to specific issues; and the experience of those who are most directly affected by the manual by being diagnosed, including the consumer/survivor movement.[71][72][73][74]

Treatment

[edit]General considerations

[edit]

Individuals receiving psychiatric treatment are commonly referred to as patients but may also be called clients, consumers, or service recipients. They may come under the care of a psychiatric physician or other psychiatric practitioners by various paths, the two most common being self-referral or referral by a primary care physician. Alternatively, a person may be referred by hospital medical staff, by court order, involuntary commitment, or, in countries such as the UK and Australia, by sectioning under a mental health law.

A psychiatrist or medical provider evaluates people through a psychiatric assessment for their mental and physical condition. This usually involves interviewing the person and often obtaining information from other sources such as other health and social care professionals, relatives, associates, law enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, and psychiatric rating scales. A mental status examination is carried out, and a physical examination is usually performed to establish or exclude other illnesses that may be contributing to the alleged psychiatric problems. A physical examination may also serve to identify any signs of self-harm; this examination is often performed by someone other than the psychiatrist, especially if blood tests and medical imaging are performed.

Like most medications, psychiatric medications can cause adverse effects in patients, and some require ongoing therapeutic drug monitoring, for instance full blood counts, serum drug levels, renal function, liver function or thyroid function. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes administered for serious conditions, such as those unresponsive to medication. The efficacy[75][76] and adverse effects of psychiatric drugs may vary from patient to patient.

Inpatient treatment

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Psychiatric treatments have changed over the past several decades. In the past, psychiatric patients were often hospitalized for six months or more, with some cases involving hospitalization for many years.

Average inpatient psychiatric treatment stay has decreased significantly since the 1960s, a trend known as deinstitutionalization.[77][78][79][80] Today in most countries, people receiving psychiatric treatment are more likely to be seen as outpatients. If hospitalization is required, the average hospital stay is around one to two weeks, with only a small number receiving long-term hospitalization.[81] However, in Japan psychiatric hospitals continue to keep patients for long periods, sometimes even keeping them in physical restraints, strapped to their beds for periods of weeks or months.[82][83]

Psychiatric inpatients are people admitted to a hospital or clinic to receive psychiatric care. Some are admitted involuntarily, perhaps committed to a secure hospital, or in some jurisdictions to a facility within the prison system. In many countries including the United States and Canada, the criteria for involuntary admission vary with local jurisdiction. They may be as broad as having a mental health condition, or as narrow as being an immediate danger to themselves or others. Bed availability is often the real determinant of admission decisions to hard pressed public facilities.

People may be admitted voluntarily if the treating doctor considers that safety is not compromised by this less restrictive option. For many years, controversy has surrounded the use of involuntary treatment and use of the term "lack of insight" in describing patients. Internationally, mental health laws vary significantly but in many cases, involuntary psychiatric treatment is permitted when there is deemed to be a significant risk to the patient or others due to the patient's illness. Involuntary treatment refers to treatment that occurs based on a treating physician's recommendations, without requiring consent from the patient.[84]

Inpatient psychiatric wards may be secure (for those thought to have a particular risk of violence or self-harm) or unlocked/open. Some wards are mixed-sex whilst same-sex wards are increasingly favored to protect women inpatients. Once in the care of a hospital, people are assessed, monitored, and often given medication and care from a multidisciplinary team, which may include physicians, pharmacists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, psychiatric social workers, occupational therapists and social workers. If a person receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital is assessed as at particular risk of harming themselves or others, they may be put on constant or intermittent one-to-one supervision and may be put in physical restraints or medicated. People on inpatient wards may be allowed leave for periods of time, either accompanied or on their own.[85]

In many developed countries there has been a massive reduction in psychiatric beds since the mid 20th century, with the growth of community care. Italy has been a pioneer in psychiatric reform, particularly through the no-restraint initiative that began nearly fifty years ago. The Italian movement, heavily influenced by Franco Basaglia, emphasizes ethical treatment and the elimination of physical restraints in psychiatric care. A study examining the application of these principles in Italy found that 14 general hospital psychiatric units reported zero restraint incidents in 2022.[86]

Standards of inpatient care remain a challenge in some public and private facilities, due to levels of funding, and facilities in developing countries are typically grossly inadequate for the same reason. Even in developed countries, programs in public hospitals vary widely. Some may offer structured activities and therapies offered from many perspectives while others may only have the funding for medicating and monitoring patients. This may be problematic in that the maximum amount of therapeutic work might not actually take place in the hospital setting. This is why hospitals are increasingly used in limited situations and moments of crisis where patients are a direct threat to themselves or others. Alternatives to psychiatric hospitals that may actively offer more therapeutic approaches include rehabilitation centers or "rehab" as popularly termed.[citation needed]

Outpatient treatment

[edit]Outpatient treatment involves periodic visits to a psychiatrist for consultation in his or her office, or at a community-based outpatient clinic. During initial appointments, a psychiatrist generally conducts a psychiatric assessment or evaluation of the patient. Follow-up appointments then focus on making medication adjustments, reviewing potential medication interactions, considering the impact of other medical disorders on the patient's mental and emotional functioning, and counseling patients regarding changes they might make to facilitate healing and remission of symptoms. The frequency with which a psychiatrist sees people in treatment varies widely, from once a week to twice a year, depending on the type, severity and stability of each person's condition, and depending on what the clinician and patient decide would be best.

Increasingly, psychiatrists are limiting their practices to psychopharmacology (prescribing medications), as opposed to previous practice in which a psychiatrist would provide traditional 50-minute psychotherapy sessions, of which psychopharmacology would be a part, but most of the consultation sessions consisted of "talk therapy". This shift began in the early 1980s and accelerated in the 1990s and 2000s.[87] A major reason for this change was the advent of managed care insurance plans,[clarification needed] which began to limit reimbursement for psychotherapy sessions provided by psychiatrists. The underlying assumption was that psychopharmacology was at least as effective as psychotherapy, and it could be delivered more efficiently because less time is required for the appointment.[88][89][90][91][a][excessive citations] Because of this shift in practice patterns, psychiatrists often refer patients whom they think would benefit from psychotherapy to other mental health professionals, e.g., clinical social workers and psychologists.[92]

Telepsychiatry

[edit]

Telepsychiatry or telemental health refers to the use of telecommunications technology (mostly videoconferencing and phone calls) to deliver psychiatric care remotely for people with mental health conditions. It is a branch of telemedicine.[93][94]

Telepsychiatry can be effective in treating people with mental health conditions. In the short-term it can be as acceptable and effective as face-to-face care.[95] Research also suggests comparable therapeutic factors, such as changes in problematic thinking or behaviour. [96]

It can improve access to mental health services for some but might also represent a barrier for those lacking access to a suitable device, the internet or the necessary digital skills. Factors such as poverty that are associated with lack of internet access are also associated with greater risk of mental health problems, making digital exclusion an important problem of telemental health services.[95]

During the COVID-19 pandemic mental health services were adapted to telemental health in high-income countries. It proved effective and acceptable for use in an emergency situation but there were concerns regarding its long-term implementation.[97]History

[edit]Earliest knowledge

[edit]The earliest known texts on mental disorders are from ancient India and include the Ayurvedic text, Charaka Samhita.[98][99] The first hospitals for curing mental illness were established in India during the 3rd century BCE.[100]

Greek philosophers, including Thales, Plato, and Aristotle (especially in his De Anima treatise), also addressed the workings of the mind. As early as the 4th century BC, the Greek physician Hippocrates theorized that mental disorders had physical rather than supernatural causes. In 387 BCE, Plato suggested that the brain is where mental processes take place. In 4th to 5th century B.C. Greece, Hippocrates wrote that he visited Democritus and found him in his garden cutting open animals. Democritus explained that he was attempting to discover the cause of madness and melancholy. Hippocrates praised his work. Democritus had with him a book on madness and melancholy.[101] During the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin,[102] a view which existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome,[102] as well as Egyptian regions.[103][page needed] Alcmaeon, believed the brain, not the heart, was the "organ of thought". He tracked the ascending sensory nerves from the body to the brain, theorizing that mental activity originated in the CNS and that the cause of mental illness resided within the brain. He applied this understanding to classify mental diseases and treatments.[17][104] Religious leaders often turned to versions of exorcism to treat mental disorders often utilizing methods that many consider to be cruel or barbaric methods. Trepanning was one of these methods used throughout history.[102]

In the 6th century AD, Lin Xie carried out an early psychological experiment, in which he asked people to draw a square with one hand and at the same time draw a circle with the other (ostensibly to test people's vulnerability to distraction). It has been cited that this was an early psychiatric experiment.[105]

The Islamic Golden Age fostered early studies in Islamic psychology and psychiatry, with many scholars writing about mental disorders. The Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi, also known as "Rhazes", wrote texts about psychiatric conditions in the 9th century.[106] As chief physician of a hospital in Baghdad, he was also the director of one of the first bimaristans in the world.[106]

The first bimaristan was founded in Baghdad in the 9th century, and several others of increasing complexity were created throughout the Arab world in the following centuries. Some of the bimaristans contained wards dedicated to the care of mentally ill patients.[107] During the Middle Ages, Psychiatric hospitals and lunatic asylums were built and expanded throughout Europe. Specialist hospitals such as Bethlem Royal Hospital in London were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders, but were used only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment. It is the oldest extant psychiatric hospital in the world.[108]

An ancient text known as The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine identifies the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation, includes theories of personality based on yin–yang balance, and analyzes mental disorder in terms of physiological and social disequilibria. Chinese scholarship that focused on the brain advanced during the Qing Dynasty with the work of Western-educated Fang Yizhi (1611–1671), Liu Zhi (1660–1730), and Wang Qingren (1768–1831). Wang Qingren emphasized the importance of the brain as the center of the nervous system, linked mental disorder with brain diseases, investigated the causes of dreams, insomnia, psychosis, depression and epilepsy.[105]

Medical specialty

[edit]The beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century,[109] although its germination can be traced to the late eighteenth century. In the late 17th century, privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. In 1713, the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose-built asylum in England.[110] In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those with mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.[111]

During the Enlightenment, attitudes towards the mentally ill began to change. It came to be viewed as a disorder that required compassionate treatment. In 1758, English physician William Battie wrote his Treatise on Madness on the management of mental disorder. It was a critique aimed particularly at the Bethlem Royal Hospital, where a conservative regime continued to use barbaric custodial treatment. Battie argued for a tailored management of patients entailing cleanliness, good food, fresh air, and distraction from friends and family. He argued that mental disorder originated from dysfunction of the material brain and body rather than the internal workings of the mind.[112][113]

The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker William Tuke.[102] In 1792, Pinel became the chief physician at the Bicêtre Hospital. Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pinel's student and successor, Jean Esquirol (1772–1840), went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles.[114]

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread into the 19th century. At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with—a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839, Sergeant John Adams and Dr. John Conolly were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their Hanwell Asylum, by then the largest in the country.[115][116][page needed]

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19th century with a large state-led effort. In England, the Lunacy Act 1845 was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of mentally ill people to patients who required treatment. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified physician.[117][full citation needed] In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country.

In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The Utica State Hospital was opened around 1850. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the Kirkbride Plan, an architectural style meant to have curative effect.[118][page needed]

At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.[119] By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. However, the idea that mental illness could be ameliorated through institutionalization ran into difficulties.[120] Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever-increasing patient population,[120] and asylums again became almost indistinguishable from custodial institutions.[121]

In the early 1800s, psychiatry made advances in the diagnosis of mental illness by broadening the category of mental disease to include mood disorders, in addition to disease level delusion or irrationality.[122] The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world, with different perspectives of looking at mental disorders. For Emil Kraepelin, the initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders are all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves", and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.[123] Following Sigmund Freud's pioneering work, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root in psychiatry.[124] The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.[124]

By the 1970s, however, the psychoanalytic school of thought became marginalized within the field.[124] Biological psychiatry reemerged during this time. Psychopharmacology and neurochemistry became the integral parts of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter. Subsequently, it has been shown that different neurotransmitters have different and multiple functions in regulation of behaviour. In a wide range of studies in neurochemistry using human and animal samples, individual differences in neurotransmitters' production, reuptake, receptors' density and locations were linked to differences in dispositions for specific psychiatric disorders. For example, the discovery of chlorpromazine's effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disorder,[125] as did lithium carbonate's ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in bipolar disorder in 1948.[126] Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.[127] This proved the idea of neurochemical nature of many psychiatric disorders.

Another approach to look for biomarkers of psychiatric disorders is [128] Neuroimaging that was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.[129]

In 1963, US president John F. Kennedy introduced legislation delegating the National Institute of Mental Health to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.[130] Later, though, the Community Mental Health Centers focus shifted to providing psychotherapy for those with acute but less serious mental disorders.[130] Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively following and treating severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals, resulting in a large population of chronically homeless people with mental illness.[130]

Controversy and criticism

[edit]The institution of psychiatry has attracted controversy since its inception.[131]: 47 Scholars including those from social psychiatry, psychoanalysis, psychotherapy, and critical psychiatry have produced critiques.[131]: 47 It has been argued that psychiatry confuses disorders of the mind with disorders of the brain that can be treated with drugs;[131]: 53 : 47 that its use of drugs is in part due to lobbying by drug companies resulting in distortion of research;[131]: 51 and that the concept of "mental illness" is often used to label and control those with beliefs and behaviours that the majority of people disagree with;[131]: 50 and that it is too influenced by ideas from medicine causing it to misunderstand the nature of mental distress.[131] Critique of psychiatry from within the field comes from the critical psychiatry group in the UK.

Double argues that most critical psychiatry is anti-reductionist. Rashed argues new mental health science has moved beyond this reductionist critique by seeking integrative and biopsychosocial models for conditions and that much of critical psychiatry now exists with orthodox psychiatry but notes that many critiques remain unaddressed[132]: 237

The term anti-psychiatry was coined by psychiatrist David Cooper in 1967 and was later made popular by Thomas Szasz. The word Antipsychiatrie was already used in Germany in 1904.[133] The basic premise of the anti-psychiatry movement is that psychiatrists attempt to classify "normal" people as "deviant"; psychiatric treatments are ultimately more damaging than helpful to patients; and psychiatry's history involves (what may now be seen as) dangerous treatments, such as psychosurgery an example of this being the frontal lobectomy (commonly called a lobotomy).[134] The use of lobotomies largely disappeared by the late 1970s.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ This article does not enter into that debate or seek to summarize the comparative efficacy literature. It simply explains why managed care insurance companies stopped routinely reimbursing psychiatrists for traditional psychotherapy, without commenting on the validity of that rationale.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Backes KA, Borges NJ, Binder SB, Roman BJ (2013). "First-year medical student objective structured clinical exam performance and specialty choice". International Journal of Medical Education. 4: 38–40. doi:10.5116/ijme.5103.b037.

- ^ Alarcón RD (2016). "Psychiatry and Its Dichotomies". Psychiatric Times. 33 (5): 1. Archived from the original on 2019-01-30. Retrieved 2016-07-26.

- ^ a b "Information about Mental Illness and the Brain (Page 3 of 3)". The Science of Mental Illness. National Institute of Mental Health. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ^ First, M; Rebello, T; Keeley, J; Bhargava, R; Dai, Y; Kulygina, M; Matsumoto, C; Robles, R; Stona, A; Reed, G (June 2018). "Do mental health professionals use diagnostic classifications the way we think they do? A global survey". World Psychiatry. 17 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1002/wps.20525. PMC 5980454. PMID 29856559.

- ^ Kupfer DJ, Regier DA (May 2010). "Why all of medicine should care about DSM-5". JAMA. 303 (19): 1974–5. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.646. PMID 20483976.

- ^ Gabbard GO (February 2007). "Psychotherapy in psychiatry". International Review of Psychiatry. 19 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1080/09540260601080813. PMID 17365154. S2CID 25268111.

- ^ "Psychiatry Specialty Description". American Medical Association. Archived from the original on 12 October 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Rabuzzi M (November 1997). "Butterfly Etymology". Cultural Entomology Digest. No. 4. Archived from the original on 3 December 1998.

- ^ James FE (July 1991). "Psyche". Psychiatric Bulletin. 15 (7): 429–31. doi:10.1192/pb.15.7.429.

- ^ Guze 1992, p. 4.

- ^ a b Storrow HA (1969). Outline of Clinical Psychiatry. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-390-85075-1. OCLC 599349242.

- ^ Lyness 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 7.

- ^ Guze 1992, p. 131.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 113.

- ^ Gask 2004, p. 128.

- ^ a b c Pietrini P (November 2003). "Toward a biochemistry of mind?". Editorial. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1907–8. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1907. PMID 14594732.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 326.

- ^ "Specialty and Subspecialty Certificates", American Board of Medical Specialties, n.d., archived from the original on 23 January 2020, retrieved 27 July 2016

- ^ Hauser MJ. "Student Information". Psychiatry.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ^ "Handbook of Interventional Psychiatry - Handbook of Interventional Psychiatry". interventionalpsych.org. 2024-07-27. Retrieved 2024-08-28.

- ^ a b "Madrid Declaration on Ethical Standards for Psychiatric Practice". World Psychiatric Association. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Alamo C, Dudley M, Rubio G, García-García P, Molina JD, Okasha A (May 2007). "Psychiatry and political-institutional abuse from the historical perspective: the ethical lessons of the Nuremberg Trial on their 60th anniversary". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 31 (4). Cecilio Alamoa, Michael Dudleyb, Gabriel Rubioc, Pilar García-Garcíaa, Juan D. Molinad and Ahmed Okasha: 791–806. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.12.007. PMID 17223241. S2CID 39675837.

These practices, in which racial hygiene constituted one of the fundamental principles and euthanasia programmes were the most obvious consequence, violated the majority of known bioethical principles. Psychiatry played a central role in these programmes, and the mentally ill were the principal victims.

- ^ Gluzman SF (December 1991). "Abuse of psychiatry: analysis of the guilt of medical personnel". Journal of Medical Ethics. 17 Suppl (Suppl): 19–20. doi:10.1136/jme.17.Suppl.19. PMC 1378165. PMID 1795363.

Based on the generally accepted definition, we correctly term the utilisation of psychiatry for the punishment of political dissidents as torture.

- ^ Debreu G (1988). "Introduction". In Corillon C (ed.). Science and Human Rights. The National Academies Press. p. 21. doi:10.17226/9733. ISBN 978-0-309-57510-2. PMID 25077249. Archived from the original on 2015-09-10. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

Over the past two decades the systematic use of torture and psychiatric abuse have been sanctioned or condoned by more than one-third of the nations in the United Nations, about half of mankind.

- ^ Kirk S, Gomory T, Cohen D (2013). Mad Science: Psychiatric Coercion, Diagnosis, and Drugs. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4128-4976-0. OCLC 935892629.

- ^ Verhulst J, Tucker G (May 1995). "Medical and narrative approaches in psychiatry". Psychiatric Services. 46 (5): 513–4. doi:10.1176/ps.46.5.513. PMID 7627683.

- ^ a b c d McLaren N (February 1998). "A critical review of the biopsychosocial model". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 32 (1): 86–92, discussion 93–6. doi:10.3109/00048679809062712. PMID 9565189. S2CID 12321002.

- ^ a b c McLaren M (2007). Humanizing Madness. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 978-1-932690-39-2.[page needed]

- ^ a b c McLaren N (2009). Humanizing Psychiatry. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 978-1-61599-011-5.[page needed]

- ^ Michael H. "Humanistic Therapy". CRC Health Group. Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ McLeod S (2014). "Psychoanalysis". Simply Psychology. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ a b Brown M, Barnes J, Silver K, Williams N, Newton PM (April 2016). "The Educational Impact of Exposure to Clinical Psychiatry Early in an Undergraduate Medical Curriculum". Academic Psychiatry. 40 (2): 274–81. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0358-1. PMID 26077010. S2CID 13274934.

- ^ Japsen B (15 September 2015). "Psychiatrist Shortage Worsens Amid 'Mental Health Crisis'". Forbes. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ Thiele JS, Doarn CR, Shore JH (June 2015). "Locum tenens and telepsychiatry: trends in psychiatric care". Telemedicine Journal and e-Health. 21 (6): 510–3. doi:10.1089/tmj.2014.0159. PMID 25764147.

- ^ Moran M (2015). "2015 Match Finds Big Jump in Students Choosing Psychiatry". Psychiatric News. 50 (8): 1. doi:10.1176/appi.pn.2015.4b15.

- ^ "Taking a Subspecialty Exam". American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2015-09-19.

- ^ "Brain Injury Medicine". American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- ^ Hausman K (6 December 2013). "Brain Injury Medicine Gains Subspecialty Status". Psychiatric News. 48 (23): 10. doi:10.1176/appi.pn.2013.11b29.

- ^ "Psychosomatic Medicine". American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- ^ "Sleep Medicine". American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. Archived from the original on 2017-08-20. Retrieved 2017-08-20.

- ^ "Careers info for School leavers". The Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2005. Archived from the original on 9 July 2007. Retrieved March 25, 2007.

- ^ "About AACP". American Association of Community Psychiatrists. University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry. Archived from the original on 6 September 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ^ Patel V, Prince M (May 2010). "Global mental health: a new global health field comes of age". Commentary. JAMA. 303 (19): 1976–7. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.616. PMC 3432444. PMID 20483977.

- ^ Mills C (2013-11-11). Decolonizing global mental health: the psychiatrization of the majority world. London. ISBN 978-1-84872-160-9. OCLC 837146781.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Watters E (2011). Crazy like us. London. ISBN 978-1-84901-577-6. OCLC 751584971.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Suman F (2010). Mental health, race and culture (3rd ed.). Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-21271-8. OCLC 455800587.

- ^ Suman F (2014-04-11). Mental health worldwide: culture, globalization and development. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire. ISBN 978-1-137-32958-5. OCLC 869802072.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Research in Psychiatry". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "New York State Psychiatric Institute". 15 March 2007. Archived from the original on 5 November 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation". 27 July 2007. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ "Journal of Psychiatric Research". Elsevier. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- ^ Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Adson DE (2000). Elements of Clinical Research in Psychiatry. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 978-0-88048-802-0. OCLC 632834662.

- ^ Meyendorf R (1980). "[Diagnosis and differential diagnosis in psychiatry and the question of situation referred prognostic diagnosis]" [Diagnosis and differential diagnosis in psychiatry and the question of situation referred prognostic diagnosis]. Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie=Archives Suisses de Neurologie, Neurochirurgie et de Psychiatrie (in German). 126 (1): 121–34. PMID 7414302.

- ^ Leigh H (1983). Psychiatry in the practice of medicine. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. pp. 15, 17, 67. ISBN 978-0-201-05456-9. OCLC 869194520.

- ^ Lyness 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Hampel H, Teipel SJ, Kötter HU, Horwitz B, Pfluger T, Mager T, Möller HJ, Müller-Spahn F (May 1997). "[Structural magnetic resonance tomography in diagnosis and research of Alzheimer type dementia]" [Structural magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and research of Alzheimer's disease]. Der Nervenarzt (in German). 68 (5): 365–78. doi:10.1007/s001150050138. PMID 9280846. S2CID 35203096.

- ^ Townsend BA, Petrella JR, Doraiswamy PM (July 2002). "The role of neuroimaging in geriatric psychiatry". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 15 (4): 427–32. doi:10.1097/00001504-200207000-00014. S2CID 147489857.

- ^ "Neuroimaging and Mental Illness: A Window Into the Brain". National Institute of Mental Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013.

- ^ Krebs MO (2005). "Future contributions on genetics". The World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 6 (Sup 2): 49–55. doi:10.1080/15622970510030072. PMID 16166024. S2CID 44658585.

- ^ Hensch T, Herold U, Brocke B (August 2007). "An electrophysiological endophenotype of hypomanic and hyperthymic personality". Journal of Affective Disorders. 101 (1–3): 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.018. PMID 17207536.

- ^ Vonk R, van der Schot AC, Kahn RS, Nolen WA, Drexhage HA (July 2007). "Is autoimmune thyroiditis part of the genetic vulnerability (or an endophenotype) for bipolar disorder?". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (2): 135–40. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.041. PMID 17141745. S2CID 23676927.

- ^ Low DM, Bentley KH, Ghosh, SS (2020). "Automated assessment of psychiatric disorders using speech: A systematic review". Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. 5 (1): 96–116. doi:10.1002/lio2.354. PMC 7042657. PMID 32128436.

- ^ First MB, Drevets WC, Carter C, Dickstein DP, Kasoff L, Kim KL, et al. (September 2018). "Clinical Applications of Neuroimaging in Psychiatric Disorders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 175 (9): 915–916. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.1750701. PMC 6583905. PMID 30173550.

- ^ "ICD-11". icd.who.int. Retrieved 2024-01-24.

- ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th, text revision ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89042-025-6.

- ^ Chen YF (March–June 2002). "Chinese classification of mental disorders (CCMD-3): towards integration in international classification". Psychopathology. 35 (2–3): 171–5. doi:10.1159/000065140. PMID 12145505. S2CID 24080102.

- ^ Essen-Möller E (September 1961). "On classification of mental disorders". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 37 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1961.tb06163.x. S2CID 145140298.

- ^ Mezzich JE (February 1979). "Patterns and issues in multiaxial psychiatric diagnosis". Psychological Medicine. 9 (1): 125–137. doi:10.1017/S0033291700021632. PMID 370861. S2CID 44798734.

- ^ Guze SB (June 1970). "The need for toughmindedness in psychiatric thinking". Southern Medical Journal. 63 (6): 662–671. doi:10.1097/00007611-197006000-00012. PMID 5446229. S2CID 26516651.

- ^ Dalal PK, Sivakumar T (October–December 2009). "Moving towards ICD-11 and DSM-V: Concept and evolution of psychiatric classification". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (4): 310–9. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.58302. PMC 2802383. PMID 20048461.

- ^ Kendell R, Jablensky A (January 2003). "Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (1): 4–12. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4. PMID 12505793.

- ^ Baca-Garcia E, Perez-Rodriguez MM, Basurte-Villamor I, Fernandez del Moral AL, Jimenez-Arriero MA, Gonzalez de Rivera JL, Saiz-Ruiz J, Oquendo MA (March 2007). "Diagnostic stability of psychiatric disorders in clinical practice". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 190 (3): 210–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024026. PMID 17329740.

- ^ Pincus HA, Zarin DA, First M (December 1998). ""Clinical significance" and DSM-IV". Letters to the Editor. Archives of General Psychiatry. 55 (12): 1145, author reply 1147–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1145. PMID 9862559.

- ^ Moncrieff J, Wessely S, Hardy R (26 January 2004). "Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (1): CD003012. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003012.pub2. PMC 8407353. PMID 14974002.

- ^ Hopper K, Wanderling J (January 2000). "Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia" (PDF). Schizophrenia Bulletin. 26 (4): 835–46. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498. PMID 11087016.

- ^ Fisher, William H., Jeffrey L. Geller, and Dana L. McMannus. "Same Problem, Different Century: Issues in Recreating the Functions of State Psychiatric Hospitals in Community-Based Settings". In 50 Years after Deinstitutionalization: Mental Illness in Contemporary Communities, edited by Brea L. Perry, 3–25. Vol. 17 of Advances in Medical Sociology. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing, 2016. doi:10.1108/amso ISSN:1057-6290

- ^ Lutterman, Ted; Shaw, Robert; Fisher, William; Manderscheid, Ronald (2017). Trend in Psychiatric Inpatient Capacity, United States and Each State, 1970 to 2014 (PDF) (Report). Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-01.

- ^ Bao Y, Sturm R (June 2001). "How do Trends for Behavioral Health Inpatient Care Differ from Medical Inpatient Care in U.S. Community Hospitals?" (PDF). The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics. 4 (2): 55–63. PMID 11967466. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-04. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- ^ Mechanic D, McAlpine DD, Olfson M (September 1998). "Changing patterns of psychiatric inpatient care in the United States, 1988–1994". Archives of General Psychiatry. 55 (9): 785–791. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.785. PMID 9736004.

- ^ Lee S, Rothbard AB, Noll EL (September 2012). "Length of inpatient stay of persons with serious mental illness: effects of hospital and regional characteristics". Psychiatric Services. 63 (9): 889–895. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201100412. PMID 22751995.

- ^ "Number of patients physically restrained at psychiatric hospitals soars". The Japan Times Online. 2016-05-09. Archived from the original on 2023-03-11. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- ^ 長谷川利夫. (2016). 精神科医療における隔離・ 身体拘束実態調査 ~その急増の背景要因を探り縮減への道筋を考える~. 病院・地域精神医学, 59(1), 18–21.

- ^ Unzicker R, Wolters KP, Robinson DE (20 January 2000). "From Privileges to Rights: People Labeled with Psychiatric Disabilities Speak for Themselves". National Council on Disability. Archived from the original on 28 December 2010.

- ^ Treatment Protocol Project (2003). Acute inpatient psychiatric care: A source book. Darlinghurst, Australia: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-0-9578073-1-0. OCLC 223935527.

- ^ Pocobello, Raffaella; Camilli, Francesca; Rossi, Giovanni; Davì, Maurizio; Corbascio, Caterina; Tancredi, Domenico; Oretti, Alessandra; Bonavigo, Tommaso; Galeazzi, Gian Maria; Wegenberger, Oliver; el Sehity, Tarek (January 2024). "No-Restraint Committed General Hospital Psychiatric Units (SPDCs) in Italy—A Descriptive Organizational Study". Healthcare. 12 (11): 1104. doi:10.3390/healthcare12111104. ISSN 2227-9032. PMC 11171828. PMID 38891179.

- ^ Mojtabai R, Olfson M (August 2008). "National trends in psychotherapy by office-based psychiatrists". Archives of General Psychiatry. 65 (8): 962–70. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.8.962. PMID 18678801.

- ^ Clemens NA (March 2010). "New parity, same old attitude towards psychotherapy?". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 16 (2): 115–9. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000369972.10650.5a. PMID 20511735.

- ^ Mellman LA (March 2006). "How endangered is dynamic psychiatry in residency training?". The Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry. 34 (1): 127–33. doi:10.1521/jaap.2006.34.1.127. PMID 16548751.

- ^ Mojtabai R, Olfson M (January 2010). "National trends in psychotropic medication polypharmacy in office-based psychiatry". Archives of General Psychiatry. 67 (1): 26–36. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.175. PMID 20048220.

- ^ Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA (January 2002). "National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression". JAMA. 287 (2): 203–9. doi:10.1001/jama.287.2.203. PMID 11779262.

- ^ Harris G (March 5, 2011). "Talk Doesn't Pay, So Psychiatry Turns to Drug Therapy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ^ "What is Telepsychiatry?". American Psychiatric Association. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ^ "What is Telemental Health?". National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ^ a b Schlief, Merle; Saunders, Katherine R K; Appleton, Rebecca; Barnett, Phoebe; Vera San Juan, Norha; Foye, Una; Olive, Rachel Rowan; Machin, Karen; Shah, Prisha; Chipp, Beverley; Lyons, Natasha; Tamworth, Camilla; Persaud, Karen; Badhan, Monika; Black, Carrie-Ann (2022-09-29). "Synthesis of the Evidence on What Works for Whom in Telemental Health: Rapid Realist Review". Interactive Journal of Medical Research. 11 (2): e38239. doi:10.2196/38239. ISSN 1929-073X. PMC 9524537. PMID 35767691.

- ^ Schuster, Raphael; Fischer, Elena; Jansen, Chiara; Napravnik, Nathalie; Rockinger, Susanne; Steger, Nadine; Laireiter, Anton-Rupert (2022). "Blending Internet-based and tele group treatment: Acceptability, effects, and mechanisms of change of cognitive behavioral treatment for depression". Internet Interventions. 29. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2022.100551. PMC 9204733. PMID 35722084.

- ^ Appleton, Rebecca; Williams, Julie; Vera San Juan, Norha; Needle, Justin J; Schlief, Merle; Jordan, Harriet; Sheridan Rains, Luke; Goulding, Lucy; Badhan, Monika; Roxburgh, Emily; Barnett, Phoebe; Spyridonidis, Spyros; Tomaskova, Magdalena; Mo, Jiping; Harju-Seppänen, Jasmine (2021-12-09). "Implementation, Adoption, and Perceptions of Telemental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review". Journal of Medical Internet Research. 23 (12): e31746. doi:10.2196/31746. ISSN 1438-8871. PMC 8664153. PMID 34709179.

- ^ Scull A, ed. (2014). Cultural Sociology of Mental Illness: An A-to-Z Guide. Vol. 1. SAGE Publications. p. 386. ISBN 978-1-4833-4634-2. OCLC 955106253.

- ^ Levinson D, Gaccione L (1997). Health and Illness: A Cross-cultural Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-87436-876-5. OCLC 916942828.

- ^ Koenig HG (2005). "History of Mental Health Care". Faith and Mental Health: Religious Resources for Healing. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-59947-078-8. OCLC 476009436.

- ^ Burton R (1881). The Anatomy of Melancholy: What it is with All the Kinds, Causes, Symptoms, Prognostics, and Several Cures of it: in Three Partitions, with Their Several Sections, Members and Subsections Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically Opened and Cut Up. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 22, 24. OL 3149647W.

- ^ a b c d Elkes A, Thorpe JG (1967). A Summary of Psychiatry. London: Faber & Faber. p. 13. OCLC 4687317.

- ^ Dumont F (2010). A history of personality psychology: Theory, science and research from Hellenism to the twenty-first century. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11632-9. OCLC 761231096.

- ^ Janssen, Diederik F.; Hubbard, Thomas K. (May 2021). "Psychology: Early print uses of the term by Pier Nicola Castellani (1525) and Gerhard Synellius (1525)". History of Psychology. 24 (2): 182–187. doi:10.1037/hop0000187. ISSN 1939-0610. PMID 34081519. S2CID 235334263.

- ^ a b Janssen, Diederik F.; Hubbard, Thomas K. (May 2021). "Psychology: Early print uses of the term by Pier Nicola Castellani (1525) and Gerhard Synellius (1525)". History of Psychology. 24 (2): 182–187. doi:10.1037/hop0000187. ISSN 1939-0610. PMID 34081519. S2CID 235334263.

- ^ a b Mohamed WM (August 2008). "History of Neuroscience: Arab and Muslim Contributions to Modern Neuroscience" (PDF). International Brain Research Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2014.

- ^ Miller AC (December 2006). "Jundi-Shapur, bimaristans, and the rise of academic medical centres". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 99 (12): 615–617. doi:10.1177/014107680609901208. PMC 1676324. PMID 17139063.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 1.

- ^ "The Bethel Hospital". Norwich HEART: Heritage Economic & Regeneration Trust. Archived from the original on 13 November 2011.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 5.

- ^ Laffey P (October 2003). "Psychiatric therapy in Georgian Britain". Psychological Medicine. 33 (7): 1285–97. doi:10.1017/S0033291703008109. PMID 14580082. S2CID 13162025.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 9.

- ^ Gerard DL (September 1997). "Chiarugi and Pinel considered: Soul's brain/person's mind". Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences. 33 (4): 381–403. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6696(199723)33:4<381::AID-JHBS3>3.0.CO;2-S.[dead link]

- ^ Suzuki A (January 1995). "The politics and ideology of non-restraint: the case of the Hanwell Asylum". Medical History. 39 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1017/s0025727300059457. PMC 1036935. PMID 7877402.

- ^ Bynum WF, Porter R, Shepherd M, eds. (1988). The Asylum and its psychiatry. The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry. Vol. 3. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00859-4. OCLC 538062123.

- ^ Wright, David: "Mental Health Timeline", 1999

- ^ Yanni C (2007). The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4939-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 34.

- ^ a b Shorter 1997, p. 46.

- ^ Rothman DJ (1990). The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little Brown. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-316-75745-4.

- ^ Borch-Jacobsen M (7 October 2010). "Which came first, the condition or the drug?". London Review of Books. 32 (19): 31–33. Archived from the original on 13 March 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Shorter 1997, p. 145.

- ^ Turner T (January 2007). "Chlorpromazine: unlocking psychosis". BMJ. 334 (Suppl 1): s7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. PMID 17204765.

- ^ Cade JF (September 1949). "Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement". The Medical Journal of Australia. 2 (10): 349–52. doi:10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.06241.x. PMC 2560740. PMID 18142718.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 239.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 246.

- ^ Shorter 1997, p. 270.

- ^ a b c Shorter 1997, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d e f Middleton H, Moncrieff J (2019). "Critical psychiatry: a brief overview". BJPsych Advances. 25: 47–54. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.38. S2CID 149547063.

- ^ Rashed MA (2020). "The critique of psychiatry as we enter the third decade of the 21st century: Commentary on… Critical psychiatry". BJPsych Bulletin. 44 (6): 236–238. doi:10.1192/bjb.2020.10. ISSN 2056-4694. PMC 7684776. PMID 32102717.

- ^ Bangen, Hans: Geschichte der medikamentösen Therapie der Schizophrenie. Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-927408-82-4, page 87

- ^ "Citizens Commission on Human Rights Expands its Activities to Expose and Handle Psychiatric Abuse in Clearwater, Tampa Bay via New Center". Scientology. Archived from the original on 2018-03-11. Retrieved 2018-03-10.

Cited texts

[edit]- Gask L (2004). A Short Introduction to Psychiatry. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7619-7138-2. OCLC 56009828.

- Guze SB (1992). Why Psychiatry Is a Branch of Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507420-8. OCLC 25315637.

- Lyness JM (1997). Psychiatric Pearls. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-0280-9. OCLC 807453406.

- Shorter, E (1998) [1997]. A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-471-24531-5. OCLC 60169541.

Further reading

[edit]- Berrios GE, Porter R, eds. (1995). The History of Clinical Psychiatry. London: Athlone Press. ISBN 978-0-485-24211-9. OCLC 1000559759.

- Berrios GE (1996). History of Mental symptoms: The History of Descriptive Psychopathology since the 19th century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-52672-5. OCLC 668203298.

- Burke C (February 2000). "Psychiatry: a "value-free" science?". Linacre Quarterly. 67/1: 59–88. doi:10.1080/20508549.2000.11877569. S2CID 77216987. Archived from the original on 2021-11-29. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- Ford-Martin PA (2002). "Psychosis". In Longe JL, Blanchfield DS (eds.). Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Vol. 4 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Gale Group. OCLC 51166617.

- Francis, Gavin, "Changing Psychiatry's Mind" (review of Anne Harrington, Mind Fixers: Psychiatry's Troubled Search for the Biology of Mental Illness, Norton, 366 pp.; and Nathan Filer, This Book Will Change Your Mind about Mental Health: A Journey into the Heartland of Psychiatry, London, Faber and Faber, 248 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXVIII, no. 1 (14 January 2021), pp. 26–29. "[M]ental disorders are different [from illnesses addressed by other medical specialties].... [T]o treat them as purely physical is to misunderstand their nature." "[C]are [needs to be] based on distress and [cognitive, emotional, and physical] need rather than [on psychiatric] diagnos[is]", which is often uncertain, erratic, and unreplicable. (p. 29.)

- Halpern, Sue, "The Bull's-Eye on Your Thoughts" (review of Nita A. Farahany, The Battle for Your Brain: Defending the Right to Think Freely in the Age of Neurotechnology, St. Martin's, 2023, 277 pp.; and Daniel Barron, Reading Our Minds: The Rise of Big Data Psychiatry, Columbia Global Reports, 2023, 150 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 17 (2 November 2023), pp. 60–62. Psychiatrist Daniel Barron deplores psychiatry's reliance largely on subjective impressions of a patient's condition – on behavioral-pattern recognition – whereas other medical specialties dispose of a more substantial armamentarium of objective diagnostic technologies. A psychiatric patient's diagnoses are arguably more in the eye of the physician: "An anti-psychotic 'works' if a [psychiatric] patient looks and feels less psychotic." Barron also posits that talking – an important aspect of psychiatric diagnostics and treatment – involves vague, subjective language and therefore cannot reveal the brain's objective workings. He trusts, though, that Big Data technologies will make psychiatric signs and symptoms more quantifiably objective. Sue Halpern cautions, however, that "When numbers have no agreed-upon, scientifically-derived, extrinsic meaning, quantification is unavailing." (p. 62.)

- Hirschfeld RM, Lewis L, Vornik LA (February 2003). "Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come? Results of the national depressive and manic-depressive association 2000 survey of individuals with bipolar disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 (2): 161–74. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0209. PMID 12633125.

- Hiruta G (June 2002). Beveridge A (ed.). "Japanese psychiatry in the Edo period (1600-1868)". History of Psychiatry. 13 (50): 131–51. doi:10.1177/0957154X0201305002. S2CID 143377079.

- Krieke LV, Jeronimus BF, Blaauw FJ, Wanders RB, Emerencia AC, Schenk HM, Vos SD, Snippe E, Wichers M, Wigman JT, Bos EH, Wardenaar KJ, Jonge PD (June 2016). "HowNutsAreTheDutch (HoeGekIsNL): A crowdsourcing study of mental symptoms and strengths" (PDF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 25 (2): 123–44. doi:10.1002/mpr.1495. hdl:11370/060326b0-0c6a-4df3-94cf-3468f2b2dbd6. PMC 6877205. PMID 26395198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-02. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- McGorry PD, Mihalopoulos C, Henry L, Dakis J, Jackson HJ, Flaum M, Harrigan S, McKenzie D, Kulkarni J, Karoly R (February 1995). "Spurious precision: procedural validity of diagnostic assessment in psychotic disorders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (2): 220–3. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.469.3360. doi:10.1176/ajp.152.2.220. PMID 7840355.

- Moncrieff J, Cohen D (2005). "Rethinking models of psychotropic drug action". Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 74 (3): 145–53. doi:10.1159/000083999. PMID 15832065. S2CID 6917144.

- Singh, Manvir, "Read the Label: How psychiatric diagnoses create identities", The New Yorker, 13 May 2024, pp. 20-24. "[T]he Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM [...] guides how Americans [...] understand and deal with mental illness. [...] The DSM as we know it appeared in 1980, with the publication of the DSM-III [which] favored more precise diagnostic criteria and a more scientific approach [than the first two DSM editions]. [H]owever, the emerging picture is of overlapping conditions, of categories that blur rather than stand apart. No disorder has been tied to a specific gene or set of genes. Nearly [p. 20] all genetic vulnerabilities implicated in mental illness have been associated with many conditions. [...] As the philosopher Ian Hacking observed, labelling people is very different from labelling quarks or microbes. Quarks and microbes are indifferent to their labels; by contrast, human classifications change how 'individuals experience themselves – and may even lead people to evolve their feelings and behavior in part because they are so classified.' Hacking's best-known example is multiple personality disorder [now called dissociative identity disorder]. Between 1972 and 1986, the number of cases of patients with multiple personalities exploded from the double digits to an estimated six thousand. [...] [I]n 1955 [n]o such diagnosis [had] existed. [Similarly, o]ver the past twenty years, the prevalence of autism in the United States has quadrupled [...]. A major driver of this surge has been a broadening of the definition and a lowering of the diagnostic threshold. Among people diagnosed with autism [...] evidence of the psychological and neurological traits associated with the condition declined by up to eighty per cent between 2000 and 2015. Temple Grandin [has commented that] [p. 21] 'The spectrum is so broad it doesn't make much sense.' [Confusion has also surrounded the term "sociopathy", which] was dropped from the DSM-II with the arrival of 'antisocial personality disorder' [...]. Some scholars associated sociopathy with remorseless and impulsive behavior caused by a brain injury. Other people associated it with an antisocial personality. [T]he psychologist Martha Stout used it to mean a lack of conscience." (p. 22.) Yet another confusing nosological entity is borderline personality disorder, "defined by sudden swings in mood, self-image, and perceptions of others. [...] The concept is generally attributed to the psychoanalyst Adolph Stern, who used it in 1937 to describe patients who were neither neurotic nor psychotic and thus [were] 'borderline.' [It has been noted that] key symptoms such as identity disturbance, outbursts of anger, and unstable interpersonal relations also feature in narcissistic and histrionic personality disorders. [Medical sociologist] Allan Horwitz [...] asks why the DSM still treats B.P.D. as a disorder of personality rather than of mood. [p. 23.] [T]he process of labelling reifies categories [that is, endows them with a deceptive quality of "thingness"], especially in the age of the Internet. [...] [P]eople everywhere encounter models of illness that they unconsciously embody. [...] In 2006, a [Mexican] student [...] developed devastating leg pain and had trouble walking; soon hundreds of classmates were afflicted." (p. 24.)

- "What is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?". National Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists. Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 20 September 2006.

- Van Os J, Gilvarry C, Bale R, Van Horn E, Tattan T, White I, Murray R (May 1999). "A comparison of the utility of dimensional and categorical representations of psychosis. UK700 Group". Psychological Medicine. 29 (3): 595–606. doi:10.1017/s0033291798008162. PMID 10405080. S2CID 38854519.

- Walker E, Young PD (1986). A Killing Cure (1st ed.). New York: H. Holt and Co. ISBN 978-0-03-069906-1. OCLC 12665467.

- Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, Spitzer RL, Davies M, Borus J, Howes MJ, Kane J, Pope HG, Rounsaville B (August 1992). "The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability". Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (8): 630–6. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820080038006. PMID 1637253.