Punsch

Punsch (or punssi in Finnish) is a type of liqueur popular in Sweden and Finland. It is most frequently called Swedish Punsch, and while historical variations have also been called Militär Punsch, Arrack Pun(s)ch, and Caloric Pun(s)ch, punsch should not be confused with the English term "punch".[1] It is made by the mixing of spirits (arrack, brandy or rum) with arrak tea (lemon and spices), sugar, and water,[2] and was first brought to Sweden from Java in 1733. The spirit arrack is the base ingredient in most punsches, also imported into Europe by the Dutch from their colony in Batavia, Dutch East Indies.[3] Punsch usually has 25% alcohol by volume (ABV) and 30% sugar.[4]

While still made in Sweden by combining ingredients, since the later part of the 19th century it is frequently purchased as a bottled liqueur under various brand names. It is drunk both warmed and chilled.

Etymology

[edit]Originally, Swedish/Finnish punsch was a variant of punch, which became a popular drink all over Europe in the 18th century, having been introduced in Britain from India in the late 17th century. Some believe the word punch/punsch came from a loanword from Persian panj, meaning "five", as punch was originally made with five ingredients: alcohol, sugar, lemon, water, and tea or spices.[5] Others believe the word originates from the English puncheon, which was a volumetric description for certain sized barrels used to transport alcohol on ships.[6][7] The English spelling of the word was in Sweden and Germany adapted to local spelling rules, thus becoming punsch.[8] In Sweden, regular punch is also served, but is instead known as bål (bowl). Punsch became such a tradition in Sweden that it influenced the language: there are some 80 words in the Swedish dictionary derived from punsch.[9]

History of punsch

[edit]

The Swedish East India Company started to import arrack with the arrival of their ship Fredricus Rex Sueciae to Gothenburg in 1733. It quickly became popular, especially among the wealthy, who could afford the price of imported spirits and teas to make punsch. Later it spread through all levels of society, including students, the military, and fraternal orders, becoming a truly national drink.[6][10]

An early recipe for punsch was written by Pehr Osbeck in the book he published with his fellow travellers Olof Torén and Carl Gustaf Ekeberg, A Voyage to China and the East Indies (1771), an English translation of the original Swedish publication of 1757:

It is known to almost every one how punch is made; but, that it may be observed for the future where it is made to its greatest perfection, I will mention the true proportion of its constituent parts. To a quart of boiling water, half a pint of arrack is taken, to which one pound of sugar, and five or six lemons, or instead of them as many tamarinds as are necessary to give it the true acidity, are added: a nutmeg is likewise grated into it. The punch, which is made for the men in our ship was heated with red hot iron balls which were thrown into it. Those who can afford it, make punch a usual drink after dinner. While we stayed in China, we drunk it at dinner instead of wine which the company allowed the first table.[11]

A testament to the widespread popularity of punsch or rack (arrack)[12] are the songs of Swedish eighteenth century poet and composer Carl Michael Bellman. It is often mentioned in his three works Bacchi Tempel (1783), Fredmans epistlar (1790) and Fredmans sånger (1791) about a group of fictional characters, drunkards, bohemians and prostitutes in contemporary Stockholm (see for example song no. 48 or epistle no. 41).[13] Many drinking songs from that period are about the consumption of punsch.[8] Swedish entertainer Povel Ramel sang about punsch in the song "Varför är där ingen is till punschen?"[14]

The high point of punsch consumption was during the late nineteenth century, when the Swedes started frequenting restaurants and loved to end their dinner with coffee and half a bottle of punsch on the table, placed in an ice bucket. The drinking of punsch was also popular at home, and outdoor porches were sometimes referred to as punschverandas, where the men drank punsch, told stories, and smoked cigars.[15][9]

Use in food and drink

[edit]

Until the 1840s, punsch was typically served warm and created just before consumption: a sugarloaf was placed upright in a large bowl, hot water was poured over it to make the sugar dissolve, and arrack, unflavoured spirits and German Rhine wine were added. Still warm, the drink was then served in cups.[10] Punsch is also used as a flavoring agent or to increase the alcohol content for glögg,[16] the warmed Scandinavian mulled wine frequently associated with Christmas. On Thursdays, punsch is traditionally served warm as an accompaniment to Swedish yellow pea and pork soup (ärtsoppa) and pancakes.[8][17][18][19] It may also be served warm at winter festivals and at student sittning dinners.

In 1845 the wine importing company J. Cederlunds Söner started selling premixed punsch in bottles. This was quickly followed by several other manufacturers, including in northern Germany,[20] and the habit of also drinking punsch as a chilled liqueur began to take hold.[8]

Apart from being drunk neat, punsch is mixed into cocktails.[21] Among the more prevalent are the Doctor cocktail (with rum & lime), the Diki-Diki (with apple brandy & grapefruit juice), and the Guldkant (or "gold rim", made with equal parts punsch & cognac).[22] Trader Vic's 1947 Bartender's Guide includes the Turret Cocktail and its version of the Corpse Reviver No.2 with Swedish punsch. Other alcoholic drinks include the Boomerang cocktail, Greta Garbo,[23] Malecon, and the Modernista.

Mixed also for wine cocktails, pre-prohibition era bartender Charles Mahoney mixed equal parts Rhine wine and punsch to make a Prefeldt Highball.[24] Punsch is also added to sparkling wine to make a punsch royale.[25]

Used as a flavoring syrup in desserts, it is a vital ingredient in the popular Swedish chocolate praline, known as punschpralin.[26] It is also used in the pastry called punschrulle,[27] and is associated with the Runeberg torte.[28] Punsch ice cream is an available flavor in Sweden.[29]

Common brands

[edit]

- Carlshamns Flaggpunsch (originally Sweden, but as of 2019[update], manufactured in Finland)

- Cederlunds Caloric (originally Sweden, but as of 2019[update], manufactured in Finland)

- Facile Punsch (Sweden)

- Trosa Punsch (Sweden)

- Helmi Arrakkipunssi (Finland)

- Kronan Swedish Punsch (Sweden)

- Roslags Punsch (Sweden)

- Bellmanpunsch (Sweden)

- Grönstedts Blå (Sweden, reintroduced in 2020)

Defunct brands

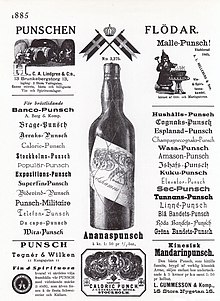

[edit]- Bil-Punsch (Automobile Punsch)

- Cirkus-Punsch

- Elevator-Punsch

- Hushålls-Punsch (Household Punsch)

- Kavalleri-Punsch (Cavalry Punsch)

- Par Bricole-Punsch

- Platins

- Skridsko-Punsch (’’Ice skate punsch’’)

- Student-Punsch

- Sport-Punsch

- Telefon-Punsch

- Velociped-Punsch (’’Bicycle punsch’’)

- Victoria-Punsch

- Lunda-punsch

References

[edit]- ^ "Punch". PunchDrink.com. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Systembolaget". Systembolaget.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ "Batavia Arrack van Oosten". Alpenz.com. Haus Alpenz. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ "Punsch". Nordiska Familjebok, Uggleupplagan (in Swedish). Vol. 22. Stockholm: Nordisk familjeboks förl. 1915. p. 609. Retrieved 7 August 2014 – via Project Runebergh.

- ^ "Punch". etymonline.com; Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ a b "Punsch, A Gift from God (translated)". naringslivshistoria.se. 4 April 2018. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "The History of Punch". diffordsguide.com. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Punsch - varm eller kall". Spritmuseum.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2014-03-04.

- ^ a b "Swedish Punsch in History". alpenz.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Punsch & Spelkort - Mera punsch". karlshamnsmuseum.se (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2014-08-09.

- ^ A Voyage to China and the East Indies by Peter Osbeck, … together with a Voyage to Suratte by Olof Toreen, chaplain of the Gothic Lion east indiaman, and an Account of the Chinese husbandry by captain Charles Gustavus Eckeberg, translated from the German, I, London, 1771, p. 318.

- ^ Bellman, Carl Michael. "N:o 9 Måltidssång" [No. 9 Meal song]. runeberg.org. Retrieved 7 August 2014 – via Project Runeberg.

- ^ "Texter och musik" [Texts and lyrics]. bellman.net. Thord Lindé. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Ramel, Povel (2007). Förflerade lingonben: åtta lådor poesi : [samlade texter] (in Swedish) ([Ny utg.] ed.). Stockholm: Fischer & Co. ISBN 978-91-85183-49-4. SELIBR 10492221.

- ^ "Punsch Veranda". punschverandan.com. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Punsch". saunalahti.fi. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ "Pea Soup and Swedish Punsch". svenskaforeningen.org.nz. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Simonson, Robert (19 May 2011). "How About a Nice Swedish Punsch?". nytimes.com. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "What should I drink in your country?". bbc.com. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Midland Druggist & Pharmaceutical Review. Columbus, Ohio: Midland Publish Company. 1909. p. 193.

- ^ "Swedish punsch cheat sheet". cocktailvirgin.blogspot.com. 19 April 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Guldkant Drink". cocktailguiden.com. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "Doctor (cocktail)". wikipedia.org. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ Mahoney, Charles (1912). Hoffman House Bartender Guide. Franklin Square, New York: Richard Fox Publishing. p. 206.

- ^ "What exactly is a Royale?". PunchDrink.com. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- ^ "Punschpralinens skapare i konkurs". aftonbladet.se (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 14 July 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Så gör du den perfekta dammsugaren". aftonbladet.se (in Swedish). Aftonbladet. 12 January 2019. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Maino, Caroline (5 February 2018). "Runebergstårta". kultursmakarna.se (in Swedish). Kultursmakarna. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ "Ice Cream Parlours in Stockholm". thatsup.co.uk. 13 September 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Fausts punschkodex: en liten bok om och till punch [Faust's punch codex: a small book about and dedicated to punch] (in Swedish) (2. uppl. ed.). 2004.