Hibachi

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (October 2023) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The hibachi (Japanese: 火鉢, fire bowl) is a traditional Japanese heating device. It is a brazier which is a round, cylindrical, or box-shaped, open-topped container, made from or lined with a heatproof material and designed to hold burning charcoal.

In North America, the term hibachi refers to a small cooking stove heated by charcoal (called a shichirin in Japanese),[1] or to an iron hot plate (called a teppan in Japanese) used in teppanyaki restaurants.[1]

There are various types of hibachi braziers, in varying shapes. They are mostly made of pottery, wood, or metal, but may also be made of stone. Hibachi also vary in size, from large and heavy to small, hand-warming braziers.

History[edit]

-

A traditional charcoal hibachi, made c. 1880–1900

-

House of the Edo period (Fukagawa Edo Museum)

-

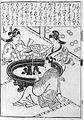

Two women and a man warming themselves by a hibachi

It is believed hibachi date back to the Heian period (794 to 1185).[1] Hibachi were first used for heating, not for cooking.[2] It heats by radiation,[3] and is too weak to warm a whole room.[4] Sometimes, people placed a tetsubin (鉄瓶, iron kettle) over the hibachi to boil water for tea.[2] Later, by the 1900s, some cooking was also done over the hibachi.[5]: 251 Hibachi were initially predominantly used by upper-class samurai and noble families because they did not produce smoke. Braziers later became popular amongst common citizens during the Edo period and Meiji period, with some were developed as interior decorations, including carved and brightly coloured ceramic braziers. [6]

Because charcoal takes time to light, and the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning and fires, braziers disappeared as stoves and other appliances became more popular during the rapid economic growth of the postwar period. [7]

Traditional Japanese houses were well ventilated (or poorly sealed), so carbon monoxide poisoning or suffocation from carbon dioxide from burning charcoal were of lesser concern.[4] Nevertheless, such risks do exist, and proper handling is necessary to avoid accidents.[5]: 255 [8] Hibachi must never be used in airtight rooms such as those in Western buildings.[8]: 129

Hibachi were produced throughout Japan, but following World War II, Shigaraki ware accounted for the majority of hibachi production. In Shigaraki, production peaked in 1949, with 300 kilns accounting for annual sales of 200 million yen.[9] As hibachi gradually became widespread in households and energy sources shifted to oil and gas, production dramatically fell.

Usage[edit]

Pebbles are placed in the bottom of the brazier, then filled more than half way with incombustible ash (typically straw ash) to act as an insulator.[4] The ash may be re-used. Wooden hibachi with a metal base are not filled with stones, which may be damp, to prevent rust.

A variety of charcoals may be used to fuel the hibachi, including both black and white charcoal. Some common premium brands are used in tea ceremonies, which light easily but burn quickly. Binchōtan, a white charcoal of oak and Ubamegashi oak, though difficult to ignite, burns slowly, making it apt for cooking.[10]

Ignition[edit]

Black charcoal is ignited in a hiokoshi and placed on top of the ash inside the brazier using a junou (a small shovel for carrying ash). In various ceremonies involving the hibachi, including in tea ceremonies, the arrangement of the charcoal is standardised.

When new coal is added to the brazier, the glowing charcoal is placed above it, so heat is transferred from the top down. To handle the charcoal, a pair of metal chopsticks called hibashi (火箸, fire chopsticks) is used, in a way similar to Western fire irons or tongs.[2]

The heat of the Hibashi is regulated by adjusting the amount of charcoal placed in the brazier, its arrangement, or by covering it in ash.

A gotoku, a plate on which metal pots or kettles can be placed, contains prongs which are buried 2-3cm into the ash for stability. This can also be used to act as a humidifier.

Safety Precautions[edit]

When charcoal burns, it produces carbon monoxide, a colourless. odourless, toxic gas which can cause carbon monoxide poisoning without proper ventilation.[11] Charcoal is also prone to bursting and producing flammable sparks. Adding hot water to ash can cause violent plumes, so iron kettles must be stabilised on a gotoku.

Using a cracked or chipped brazier can be extremely dangerous. The Great Buddha Hall of Hokoji Temple, Higashiyama, Kyoto, was destroyed in a fire during the night of March 27, 1973. The Kyoto City Fire Department determined after inspection the cause of the fire was "the careless disposal of a charcoal brazier used in the reception room on the west side of the Great Buddha Hall." There was a chip in the bottom of the brazier, causing the wooden board underneath to overheat and smoulder, starting a fire. [12]

See also[edit]

- Brazier

- Japanese traditional heating devices:

- Kamado: a kitchen stove

- Shichirin: a portable brazier

- Tabako-bon: a mini brazier to light tobacco in kiseru pipes

- Kotatsu: a covered table over a brazier

- Japanese tea utensils § Tea hearths

- Japanese cuisine

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "'Hibachi' Probably Doesn't Mean What You Think It Does". Japanese Food Guide. 5 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Hough, Walter (1928). "Collection of heating and lighting utensils in the United States National Museum". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 141. Washington D.C.: United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution: 83–84. hdl:2027/uiug.30112032539204.

- ^ Tsujimoto, Kennosuke (1935). 煖房並に台所用熱源と一酸化炭素の害毒と其の對策(其一) [Heat sources for heating and kitchen, hazards of carbon monoxide and their prevention]. Kaji to eisei (家事と衛生) (in Japanese). 11 (1): 27. doi:10.11468/seikatsueisei1925.11.25. ISSN 1883-6615. (bibliographic data:[1])

- ^ a b c Dresser, Christopher (1882). Japan: Its architecture, art, and art manufactures. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 22–23. hdl:2027/yale.39002009493082.

- ^ a b Arnold, Edwin (1904). "The Japanese Hearth". In Singleton, Esther (ed.). Japan as seen and described by famous writers. New York: Dodd, Mead and company. pp. 250–256. hdl:2027/hvd.32044013638895.

- ^ 手さげ火鉢 横須賀市教育研究所

- ^ 手さげ火鉢 横須賀市教育研究所

- ^ a b 大阪市立衛生試験所(Osaka City sanitary laboratories) (1940). 炭火中毒の話 – 一酸化炭素中毒. Kaji to eisei (家事と衛生) (in Japanese). 16 (2): 126–128. doi:10.11468/seikatsueisei1925.16.2_123. ISSN 1883-6615. (bibliographic data:[2])

- ^ "祈年祭の研究 (二) (昭和二十四年七月十二日報告)". Transactions of the Japan Academy. 7 (3): 225–238. 1949. doi:10.2183/tja1948.7.225. ISSN 0388-0036.

- ^ Guichard-Anguis, Sylvie (2011). "Walking through World Heritage Forest in Japan: the Kumano pilgrimage". Journal of Heritage Tourism. 6 (4): 285–295. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2011.620114. ISSN 1743-873X. S2CID 143584287.

- ^ 「いろり座卓使用時の一酸化炭素中毒に注意!」国民生活センター

- ^ "京都市消防局:昭和48年3月27日 東山区方広寺大仏殿炎上(写真提供:京都新聞社)". 京都市情報館 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-07-11.