Latter Days

| Latter Days | |

|---|---|

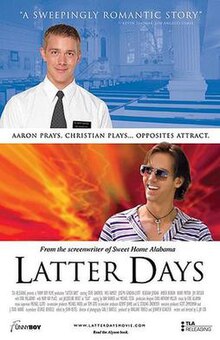

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | C. Jay Cox |

| Written by | C. Jay Cox |

| Produced by | Jennifer Schaefer Kirkland Tibbels |

| Starring | Steve Sandvoss Wes Ramsey Rebekah Johnson Jacqueline Bisset Amber Benson Joseph Gordon-Levitt Khary Payton |

| Cinematography | Carl Bartels |

| Edited by | John Keitel |

| Music by | Eric Allaman |

Production companies | Funny Boy Films Davis Entertainment Filmworks |

| Distributed by | TLA Releasing |

Release dates | |

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $850,000[2] |

| Box office | $834,685[1] |

Latter Days is a 2003 American romantic comedy drama film about the relationship between a closeted Mormon missionary and his openly gay neighbor. The film was written and directed by C. Jay Cox and stars Steve Sandvoss as the missionary, Aaron, and Wes Ramsey as the neighbor, Christian. Joseph Gordon-Levitt appears as Elder Ryder, and Rebekah Johnson as Julie Taylor. Mary Kay Place, Khary Payton, Erik Palladino, Amber Benson, and Jacqueline Bisset have supporting roles.

Latter Days premiered at the Philadelphia International Gay & Lesbian Film Festival on July 10, 2003, and was released in various states of USA over the next 12 months. Later the film was released in a few other countries and shown at several gay film festivals. It was the first film to portray openly the clash between the principles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and homosexuality, and its exhibition in some U.S. states was controversial. Various religious groups demanded that the film be withdrawn from theaters and video stores under boycott threats.

The film was met with mixed reactions from film critics, but was popular with most film festival attendees. At the North American box office however, Latter Days only made $834,685, barely covering the production's costs with an estimated budget of $850,000. In 2004, freelance writer T. Fabris made Latter Days into a novel, which was published by Alyson Publications.

Plot

[edit]Elder Aaron Davis, a young Mormon from Pocatello, Idaho, is sent to Los Angeles with three other missionaries to spread the faith. They move into an apartment next to openly gay party boy Christian Markelli and his roommate Julie, an aspiring singer. Christian and Julie work as servers at Lila's, a trendy restaurant owned by retired actress Lila Montagne.

Christian makes a bet with his co-workers that he can seduce one of the Mormons, and soon comes to believe that Aaron, the least experienced missionary, is a closeted homosexual. Aaron and Christian become acquainted through several encounters in the apartment complex. When Christian accidentally injures himself, Aaron helps him indoors and cleans his wound. Christian attempts to seduce Aaron, but the hesitant Mormon becomes upset by Christian's remark that sex "doesn't have to mean anything". Aaron accuses him of being shallow and walks out. Worried that Aaron is correct, Christian joins a charity, delivering meals to people with AIDS. He gains new insights through a friendship with one of the beneficiaries. Aaron meets and befriends Lila, whose life partner has died, unaware of her connection to Christian.

Aaron's fellow missionary, Paul Ryder, has a cycling accident. Returning to his apartment, a distraught Aaron encounters Christian, who tries to comfort him with a hug. Both men are overwhelmed by their feelings and end up kissing, failing to notice the return of Aaron's roommates. Aaron is sent home in disgrace, leading Christian to confront Ryder, who is angry that Christian corrupted Aaron for no reason. Christian admits that he initially just wanted to win a bet, but says "it's not about that" anymore. Seeing Christian's distress, Ryder tells him that Aaron's flight has a five-hour layover in Salt Lake City.

Christian finds Aaron standing outside the airport terminal. Christian confesses his love, and despite his misgivings, Aaron admits his own feelings of love. With all flights canceled due to a snowstorm, Christian and Aaron spend an intimate night in a motel. When Christian awakes, he finds Aaron gone. Aaron's pocket watch, a family heirloom, has been left behind. Christian returns to Los Angeles. In Idaho, Aaron is excommunicated by the church elders, led by his father, who is the stake president. Aaron is rejected by his father and scolded by his mother, who tells him that he must pray for forgiveness. When Aaron suggests that he might be gay, his mother slaps him. Overwhelmed by despair, Aaron attempts suicide. His parents send him to a treatment facility in an attempt to change his sexual orientation via conversion therapy.

Christian locates Aaron's home address and phone number. Aaron's mother informs him that, "Thanks to you, my son took a razor to his wrists; thanks to you I have lost my son." Believing Aaron is dead, Christian spends the next few days thinking continually about Aaron. Christian travels to the Davis home in Idaho, where he tearfully returns Aaron's watch to his mother. After looking at the watch's inscription, which mentions charity, she tries to go after Christian, but he has already left.

Julie writes a song based on Christian's journal entry about the ordeal. Julie shows Christian her video for the song, and he is upset that Julie used his writings without his consent. Julie tells Christian that she hoped something good would come from it. In the treatment facility, Aaron hears Julie's song when her video airs on television. The video prompts Aaron to return to Los Angeles in search of Christian. When a stranger answers the door to Christian's apartment, Aaron is heartbroken, thinking that Christian has returned to his party boy ways and moved on. Having nowhere else to go, Aaron makes his way to Lila's restaurant and begins to recount his journey to her. Christian walks into the dining room, and is overjoyed to see Aaron alive. They reconcile and later celebrate Thanksgiving with Christian's co-workers. Lila tells everyone that, no matter what, they will always have, "a place at my table, and a place in my heart".

Cast

[edit]

- Steve Sandvoss as Elder Aaron Davis, a young Latter-day Saint from Pocatello, Idaho, who falls in love with Christian and must choose between his sexuality and his church. The producers auditioned a large number of people before casting Sandvoss, saying he "blew us away."[3]

- Wes Ramsey as Christian William Markelli, an LA party boy aspiring to be an actor, Christian has his ideas of happiness and the meaning of life challenged when he falls for the simple but kind-hearted Aaron. Ramsey said on the DVD Special featurette, "The character of Christian was on so many levels intriguing to me. I was just so excited and feel very blessed to have the opportunity to tell that story through his eyes."[3]

- Rebekah Johnson as Julie Taylor, Christian's roommate who tries to break out into the music world and on the way stop Christian from falling apart.

- Jacqueline Bisset as Lila Montagne, the owner of Lila's, a restaurant where Christian, Traci, Julie, and Andrew work. Her lover is terminally ill in hospital, but she still finds time to support Christian and Aaron with her witty and sarcastic advice. Bisset herself said, "I like humor, so I just, I really enjoyed doing all the cracks."[3]

- Amber Benson as Traci Levine; Traci has moved from New York to LA to become an actress and works at Lila's to support herself. Traci does not like living in LA, but later admits she did not like New York much either.

- Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Elder Paul Ryder, a prickly, judgmental young missionary assigned as Aaron's partner, Ryder is not enthusiastic about being in LA and even less so about living next door to a homosexual. Gordon-Levitt originally auditioned to play Aaron, but his aggressive attitude toward the script but good sense of humor made the producers decide he was a perfect Ryder.[3]

- Khary Payton as Andrew, an aspiring actor, but one who spends more time at Lila's gossiping and telling racy anecdotes. Andrew has been HIV positive for quite some time, but remains in good health.

- Rob McElhenney as Elder Harmon, the oldest of the L.D.S. missionaries who has been assigned as their leader.

- Dave Power as Elder Gilford, Harmon's missionary partner.

- Erik Palladino as Keith Griffin, a gay man dying of AIDS, drowning in his own bitterness and despair until befriended by Christian. Cox said that Palladino's performance was not how he originally envisioned it, but he could not now imagine a different person playing Keith.[3]

- Mary Kay Place as Sister Gladys Davis, Aaron's deeply religious mother, who, despite showing unconditional love and affection toward Aaron before he leaves for Los Angeles, cannot accept the fact that her son is gay.

- Jim Ortlieb as Elder Farron Davis, Aaron's father, who serves as a Latter-day Saint Stake President in Pocatello, excommunicates Aaron from the church upon learning that he is gay. Farron is portrayed as a distant, evasive individual.

- Linda Pine as Susan Davis, the only Davis who accepts her brother's homosexuality. In a deleted scene, she tells Aaron that his homosexuality has changed nothing between them. She also discovers Aaron's suicide attempt, and in a panic, is able to save him just in time.

Themes

[edit]Cox has stated that the film is primarily about a love story between two characters.[4] There is also an exploration of religious attitudes towards homosexuality, and the dilemma of religious homosexuals, torn between who they are and what they believe. A non-fiction film with similar themes that has been contrasted with Latter Days is Trembling Before G-d.[5]

Cox has also said that there is a massive irony, both in the film and in real life, that a religion so focused on the family and its importance is ripping families apart through its teaching on homosexuality.[4] In fact, Cox believes one cannot be Mormon and gay.[6] Nevertheless, a major theme of Latter Days is that there is an underlying spirituality in the world that goes beyond the rituals and dogmas of religion.[7]

Production

[edit]Latter Days was written and directed by C. Jay Cox after the success of his previous screenplay, Sweet Home Alabama, gave him the financial resources and critical credit to write a more personal love story.[8] Cox based both characters – Christian and Aaron – on himself. He was raised as a Mormon and served a mission before coming out as gay, and had wondered what the two halves of himself would have said to each other if they had ever met.[6] Latter Days was filmed in several locations in Los Angeles in 24 days on an estimated $850,000 budget.[2] After Cox had financed the search for initial backing, funding was acquired from private investors who wanted to see the film made. However producer Kirkland Tibbels still faced several bottlenecks, as financing the whole film remained difficult.[3] It was distributed through TLA Releasing, an independent film distributor, who picked it up through its partnership with production company Funny Boy Films, which specializes in gay-themed media.[9]

Despite coming from a Mormon background, Cox had to research details of the excommunication tribunal, which is held after Aaron is sent back to Idaho. Former Mormons told him about their experiences and provided Cox with "a pretty accurate representation, right down to the folding tables."[8] According to Cox experienced actress Jacqueline Bisset also added valuable suggestions for improvements to the story.[8]

Casting for the two main characters did not focus on their sexuality, but their ability "to show vulnerability".[8] In a behind-the-scenes commentary, Steve Sandvoss explains that he did not want to play his character as a gay character, and Wes Ramsey emphasizes that the love story aspect of the film to him was detached from the character's gender.[3] Due to several nude and kissing scenes, Latter Days was released unrated.[8]

Release

[edit]Latter Days premiered at the Philadelphia International Gay and Lesbian Film Festival on July 10, 2003. The audience enjoyed the film so much that they gave it a standing ovation.[3] When the cast came on stage, they received another standing ovation. The film had a similar reception both at OutFest a week later, and at the Palm Springs International Film Festival.[3][9] The film also screened at the Seattle and Washington film festivals before being released across the United States over the following 12 months. Later the film was released in several other countries and shown at numerous gay film festivals,[10] namely in Barcelona and Madrid (where it was also a popular pick)[11] and Mexico City.[12] Since its initial release it had received nine best film awards, as Cox mentioned in 2005 on a featurette included on the UK DVD.[3]

The film was banned by Madstone Theaters, an arthouse cinema chain with nine theaters across the country, which claimed it was "not up to [our] artistic quality."[3] The company was pressured with threatened boycotts and protests by conservative groups to withdraw their planned release.[9] At the North American box office, Latter Days made $834,685 from a maximum of 19 theaters.[1] As of January 2011, the film is the top-grossing film from its distributor TLA Releasing.[13]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Critics' reviews have been mixed; on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 46% of 48 critics' reviews are positive, with an average score of 5.4/10.[14] As per Metacritic, the film has received "mixed or average reviews", with a weighted average score of 45/100 based on 21 critics' ratings.[15] Frank Scheck, reviewer for The Hollywood Reporter, wrote: "Cox's screenplay, while occasionally lapsing into the sort of clichés endemic to so many gay-themed films, generally treats its unusual subject matter with dignity and complexity."[16] Film critic Roger Ebert gave it two and a half stars out of four, declaring that the script was peopled from the "Stock Characters Store" and "the movie could have been a.) a gay love story, or b.) an attack on the Mormon Church, but is an awkward fit by trying to be c.) both at the same time."[17] Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune commented "this movie is often as kitschy and artificial as ... Sweet Home Alabama" (another film written by Cox).[18]

Other reviewers were more favourable, such as Toronto Sun critic Liz Braun, who said Latter Days was "the most important gay male movie of the past few years."[5] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times commented: "At once romantic, earthy and socially critical, Latter Days is a dynamic film filled with humor and pathos."[19] Gary Booher, an editor for the LGBTQ Mormon organization Affirmation, said "It was so realistic that it was scary. I felt exposed as the particulars of my experience and of others I know was brazenly spread across the big screen for all to behold."[20]

Awards

[edit]| Year | Festival | Award | Category |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 21. Los Angeles Lesbian and Gay Film Festival | Audience Award | Outstanding First Narrative Feature[21] |

| 2003 | 9. Philadelphia International Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature[22] |

| 2003 | 13. Washington D.C. Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature[23] |

| 2003 | 8. Seattle Lesbian & Gay Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Narrative Feature[23] |

| 2003 | 11. ImageOut Filmfestival - Rochester | Audience Award | Best Independent Feature[21] |

| 2003 | 14. Fresno Reel Pride Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature Film[23] |

| 2004 | 17. Connecticut Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature Film[24] |

| 2004 | 14. Toronto Inside Out Lesbian and Gay Film and Video Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature Film or Video[22] |

| 2004 | Lesgaicinemad (Madrid Gay & Lesbian Film Festival) | Audience Award | Best Feature Film[11] |

| 2005 | Hong Kong Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Audience Favorite[23] |

| 2005 | Outtakes New Zealand Gay & Lesbian Film Festival | Audience Award | Best Feature[23] |

Soundtrack

[edit]Eric Allaman scored the soundtrack to the film after shooting wrapped, and composed much of the score himself. Several scenes featuring the rapid passing of time, such as Christian's desperate search for Aaron at Salt Lake City Airport, were scored with techno style beats, and scenes with emotional content were given a more "ambient 'tronica feel".[3] A total of three songs were written by C. Jay Cox for Rebekah Johnson to sing: "More", "Another Beautiful Day", and "Tuesday 3:00 a.m.". Allaman was very impressed with Cox's musical ability, and both men composed more songs as background music.[3]

The official soundtrack album was released on October 26, 2004. Due to contractual reasons, Johnson did not appear on the album, and her character's songs were performed by Nita Whitaker instead.[3][25]

Novelization and other releases

[edit]In 2004, the Latter Days screenplay was adapted into a novel by freelance writer T. Fabris, which was published by Alyson Publications.[26][27] The book was faithful to the film, but added several extra scenes that explained confusing aspects of the film and gave more about the characters' backgrounds. For example, the reason Ryder tells Christian where to find Aaron is his own broken heart over a girl he fell in love with while on his mission training.[28] The novel also added dialogue that had been cut out of the film: finishing, for example Christian's cry – in the film – of "That's the hand I use to…" with "masturbate with".[29]

In France, Latter Days has been titled La Tentation d'Aaron ("The Temptation of Aaron"), and the DVD given a cover showing Aaron in a nude and suggestive pose. A new trailer was also released, which is considerably more sexual than the original.[30] In Italy, Latter Days is distributed by Fourlab. The film was re-titled Inguaribili Romantici ("Hopeless Romantics"), shown on pay-TV on Sky Show in December 2006, and then released on DVD by Fourlab's gay-themed label "OutLoud!". The film is also available in an Italian-language-dubbed version.

See also

[edit]- List of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender-related films by storyline

- Orgazmo

- The Book of Mormon (musical)

- Portrayals of Mormons in popular media

- Homosexuality and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Latter Days (2004)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Latter Days (2003) - Box office / business IMDb.com. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Latter Days DVD behind-the-scenes featurette.

- ^ a b "Cox, C. Jay -- Latter days". Killer Movie Reviews. April 2, 2004. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ a b Braun, Liz (August 16, 2004). "Love thy neighbor: Latter Days questions faith". Jam Showbiz. Archived from the original on October 22, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Phillips, Rebecca (February 12, 2004). "A Topic Deeply Buried". Beliefnet. Archived from the original on October 16, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2006.

- ^ "Latter Days". Killer Movie Reviews. December 12, 2006. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Szymanski, Mike. 'Latter Days' Director Gets Personal. Movies.zap2it.com (February 3, 2004). Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ a b c National Theater chain says "NO" to latter days. MCN Press Release (January 20, 2004). Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Release dates for Latter Days (2003). IMDb.com. Retrieved October 5, 2006.

- ^ a b "Latter Days, Implicación y Los armarios de la dictadura, premiados por el público del LesGaiCineMad 2004" (in Spanish). November 11, 2004. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ 2° Festival Internacional de Cine Gay en México en la UNAM. Retrieved January 29, 2011. (Spanish)

- ^ "TLA Releasing All time Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ "Latter Days". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ "Latter Days Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Scheck, Frank. Latter Days. The Hollywood Reporter, (February 9, 2004). Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. Latter Days. Originally published in Chicago Sun-Times, (February 13, 2004), Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ Wilmington, Michael. 'Latter Days' Chicago Tribune (February 11, 2004). Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin. Latter Days: Party boy meets Mormon missionary. What happens next overwhelms them both. Los Angeles Times, (January 30, 2004). Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Booher, Gary. "Latter Days" Is the Hit Movie at L.A. Outfest. Affirmation.org, (July 2003). Retrieved January 30, 2011.

- ^ a b "Latter Days awards", Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "TLA Releasing presents Latter Days" (PDF). TLA Releasing. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Latter Days festivals". Picture This! Entertainment. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ^ "OutFilmCT Schedule 2004". OutFilmCT. Archived from the original on November 20, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2011.

- ^ Latter Days Soundtrack. Amazon. October 12, 2004. Retrieved November 16, 2006.

- ^ Author Information: T. Fabris Archived 2008-12-20 at the Wayback Machine. IBList.com. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Latter Days: A novel, Amazon.com. Retrieved December 23, 2006.

- ^ Cox, C. Jay and Fabris, T., Latter Days: A Novel, (Alyson Publications, 2004), ISBN 1-55583-868-5, p. 160.

- ^ Latter Days: A Novel, (Alyson Publications, 2004), p. 176.

- ^ Olsen, David (April 2006). "French Translators Spice Up "Latter Days":DVD is Released in France as "La Tentation d'Aaron"". Affirmation. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

External links

[edit]- Latter Days at IMDb

- Latter Days at AllMovie

- Latter Days at Box Office Mojo

- Latter Days at Rotten Tomatoes

- Latter Days at Metacritic

- 2003 films

- 2003 LGBTQ-related films

- 2003 romantic comedy-drama films

- American independent films

- 2003 independent films

- American LGBTQ-related films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- Criticism of Mormonism

- Films about LGBTQ and Christianity

- Films about Mormonism

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Gay-related films

- Works about LGBTQ and Mormonism

- LGBTQ-related romantic comedy-drama films

- English-language romantic comedy-drama films

- Works about Mormon missionaries

- Mormonism in fiction

- HIV/AIDS in American films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s American films

- English-language independent films